"Europe would have done better to tolerate the non-European civilizations at its side, leaving them alive, dynamic, and prosperous, whole and not mutilated; that it would have been better to let them develop and fulfil themselves than to present for our admiration, duly labeled, their dead and scattered parts; that anyway, the museum by itself is nothing; that it means nothing, vanity. can say nothing, when smug self-satisfaction rots the eyes, when a secret contempt for others withers the heart, when racism, admitted or not, dries up sympathy; that it means nothing if its only purpose is to feed the delights of vanity.

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism. (1955)

We were surprised when we read in a recent report that it would be a titanic task to research the African artefacts in the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, and other French museums. (1) Are they talking about the same artefacts we looked at in the Sarr-Savoy Commission 2018 and concluded in the report, F. Sarr and B. Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage? Toward a New Relational Ethics, there was no need for further research on many artefacts since the French museums had listed all the relevant information concerning the objects they held to enable restitution. (2)

Readers will remember that President Macron of France had promised in 2017 to restitute African artefacts in French museums, and, based on the Sarr-Savoy report he commissioned, France returned to the Republic of Benin in 2021 twenty-six artefacts. (3)

Given the various debates and opposition by certain quarters to the Sarr-Savoy report, the French President requested a former director of the Louvre, Jean-Luc Martinez, to prepare another report that would propose general legislation, making it no longer necessary to produce new legislation every time countries request restitution to circumvent the rule of inalienability of state property. Jean-Luc Martinez produced a report, Shared Heritage:Universality,Restitutions,and Circulation of Works of Art.

French legislators accepted two new legislations based on the Martinez report concerning the restitution of properties seized under the antisemitic laws of the Vichy regime on July 23, 2023. (4) The second law, adopted on 26, December 2023, related to restoring human remains. (5) The third proposed legislation, also based on the Marinez report, concerning the restitution of African artefacts was to be discussed on April 2, 2023, but was postponed and withdrawn by the government because of criticisms from the Senate, which declared that for the new legislation to provide for exemption from the rule against alienability of State property, a superior ground must be established by the proposed legislation. The reasons advanced by the government, namely, the conduct of international relations and cultural cooperation, were not enough to justify derogation to the rule against alienability. The Senate raised objections to the new proposed general law and the government withdrew it.(6)

Not all looted African artefacts in French museums will require research for their restitution if we apply the criteria for restitution enunciated by the Sarr-Savoy report, which excludes from further research objects acquired through the following methods:

a. through military aggressions (spoils, trophies), whether these pieces went on directly to France or passed through the international art market before becoming integrated into collections.

b. by way of military personnel or active administrators on the continent during the colonial period (1885-1960) or by their descendants.

c. through scientific expeditions prior to 1960.

d. certain museums continue to house pieces of African origin which were initially loaned out to them by African institutions for exhibits or campaigns of restoration, but which were never given back. "

Of the 90,000 looted African artefacts said to be in French museums, at least 80,000 would fall into the categories mentioned above and would, therefore, not require any further research. What about continuing restitution with those looted treasures that require no further research? Or are there experienced French specialists who cannot identify the treasures General Amédée Dodds and his soldiers stole from the Abomey Palace in 1832? Does anybody still doubt that the French stole the Royal Dahomeyan from Dahomey?

In the stalemate created by the inability of the French Government to push through parliament new legislation on restitution and the increasing pressure of the right wing, provenance research turned out to be a valuable concept for delaying the restitution of looted African artefacts. The Germans who started discussing provenance research on African artefacts in 2015, had no difficulty transferring legal rights in 1300 to Nigeria and even physically took some Benin artefacts to Nigeria on official visits. They even borrowed Benin artefacts from Nigeria. In the meanwhile, France and Germany have set up a fund to finance provenance research. The fund will be administered by 'an independent scientific council composed of 9 personalities from academia and culture, from France, Germany and sub-Saharan Africa'. (Many Africans vehemently reject the colonialist designation ‘sub-Sahara.’) Will €2.1 million research fund be enough for work on the thousands of looted African artefacts in France and Germany? According to Bénédicte Savoy and Albert Gouaffo, Atlas der Abwesenheit, Germany holds 40,000 objects from Cameroon alone.

Nobody, not even the British Museum, will deny that most of the African artefacts in Western museums have been acquired through military force, expeditions, and other forceful and dubious means. Even the tendentious account on the homepage of the British Museum on the acquisition of the Benin bronzes does not manage to hide the aggressive military invasion of 1897.

David Wilson, Neil MacGregor's immediate predecessor as Director of the British Museum (1977–1992), admitted the acquisition of artefacts as a result of imperialist invasions:

'The Asante's skill in casting gold by the lost-wax method, and the use of elaborately worked gold to adorn the king and his servants is represented by many superb pieces which came to the Museum after British military interventions in Asante in 1874, 1896, and 1900'. (7)

French museum officials would have read accounts of French acquisition methods of colonial treasures as recounted by Michel Leiris in Afrique fantôme. (8) Violence in acquiring artefacts was an inherent quality and element of the European colonial enterprise. (9) Once you consider colonialism as a crime against humanity, it becomes difficult to justify the continuing illegal holding of colonial loot, which was only possible within the structure and conditions created by colonialism.

Emilie Salaberry, Director of the Angouleme Museum, which holds 5,000 African objects, is quoted as stating, 'Loans and long-term could be an alternative to full restitution as Britain recently did for items from the Ashanti, or Asante, the royal court in Ghana.'

The unwillingness or inability of France to return more looted African treasures renders attractive the recalcitrant attitude of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. These British museums refuse to contemplate restitution and have unashamedly pressured the Asante to accept a three-year loan of the gold artefacts the British looted in the invasion of Kumase, Ghana, in 1874. The action of the venerable British museums in restitution is an abysmal performance.

It is incredible how quickly the wrong policy of one institution can influence institutions that have followed expected policies to start doubting the legitimacy of their own previous decisions. The French, who have done the right thing in restituting looted artefacts to the Republic of Benin, now start wondering whether it might not be better to follow the British Museum, which is only ready to loan artefacts to those from whom the British army stole the treasures one hundred and fifty years ago. Other British institutions such as Jesus College, Cambridge, Horniman Museum, and Aberdeen University have returned objects to Nigeria.

Provenance research is a concept that has come at the right time, and many people appreciate its advantages for varied reasons. It has the potential to enable illegal holders of looted artefacts to delay restitution and argue they need time for research. (10)

Provenance research relieves legislators of the need to pass new laws immediately while scholars work on the subject. The scholars will be remarkably busy searching for information and knowledge. Is there any scholar who does not favour new knowledge and information that also ensures new publications?

Young scholars are grateful to be able to pursue their academic careers in projects that all will appreciate. Wealthy foundations can also invest and disburse their resources in enterprises that give them favourable reputations.

The only persons who do not benefit from the delay caused by provenance research are the original owners in Africa, who have been eagerly waiting for the restitution of their looted treasures for a hundred years. These owners are not interested in knowing whether the looted objects went to Hamburg and Heidelberg before ending in Berlin. Whether Herr Schmidt first owned the object in Hamburg, then sold it to Monsieur Moulin in Paris, who bequeathed it to his cousin Mr. Smith in London, is not essential for Chief Yaw Owusu Mensah, who is not a frequent visitor to Europe and is only interested to see the gold Asante treasures in the Asante capital.

But what is provenance research about? Many believe provenance research is about an artwork's origin and successive ownerships. A piece of African work in a Western Museum would require explaining how it landed there. Most African works in Western museums have doubtful histories and may have been acquired through force or under dubious circumstances. But who owned them before they finally entered the museum? Many African works came directly from the battlefield to their present location. For example, the pair of spotted ivory leopards in London were sent by Admiral Rawson, Commander of the invading Punitive Expedition, as soon as the British had successfully invaded Benin Kingdom in 1897. The British sold other Benin treasures at auctions in the same year to German and other European museums. Other African artefacts may have been bought in Africa and sold to collectors before they reached the museum.

Tracing the changes in the various ownerships may be necessary in a few cases. Still, the bulk of African artefacts, such as the Asante gold artefacts, the Ethiopian treasures from Maqdala, or the Benin bronzes, came from atrocious colonialist invasions. They do not need further research, and Western museums should return them to their owners in Africa.

However, we have learned from recent provenance research that the subject or provenance research goes beyond tracing ownership and extends even to the future of artefacts. (11)

But is there any legitimate reason to subordinate the restitution of African artefacts to the research of such a broad scope? Given the centuries of oppressive relations between Africa and the West, is this reasonable? Can one not research provenance in the West while the artefacts are sent to African owners? Can replicas, photos, and digitized images not be used while the original objects are with owners who must continue their lives and cultures, which were interrupted by slavery and colonialism? Most relevant documents for provenance research are in Western countries where the previous owners of looted African artefacts and their inheritors live or lived.

We should recall that provenance research is not always intended for restitution or ends in restitution. A prominent example of this comes from Hamburg. The Hamburg Kunst und Gewerbe Museum (Arts and Crafts Museum) had provenance research done on its three Benin artefacts, and the conclusion was that those artefacts were indeed part of the loot of 1897. One would have thought the museum would send the artefact to Benin City. Instead, they passed the artefacts to the MARKK – Museum at Rothenbaum, Kunst und Kulturen der Welt, because this museum already had 196 illegally held Benin artefacts and had a better framework for displaying the objects. (12) Similarly, the Dutch thoroughly researched the 196 Benin bronzes in the World Museum, Amsterdam, but have not returned these treasures to Nigeria. (13)

Emphasis on provenance research may create the impression that previous scholars, such as Felix von Luschan, did not leave much information and knowledge about the looted artefacts they first received. Luschan's authoritative work on the Benin artefacts, Die Altertümer von Benin (1919), is still a masterpiece, even if one does not share his views in concrete cases or his comments on other issues concerning Africans. German scholars are known for keeping detailed notes on whatever they do. Could the famous Ethnology professors and museum directors be exceptions?

There is sufficient information on most looted artefacts in Western museums to justify restitution to the original owners, and no attempts to hide well-known facts of history can prevent restitution. When President Macron made his famous speech at Ouagadougou in 2017, the world was inspired to believe that the centuries-old question of looted African artefacts would soon be solved. When we heard Macron's famous speech, we wrote: 'Macron would not need to worry about building monuments for his remembrance, as George Pompidou, François Mitterrand, and Jacques Chirac did. His remembrance will be written in the hearts of many Africans who will recognize his concrete contribution if he succeeds in returning a respectable portion of the thousands of African artefacts in France. ‘(14)

When the Sarr-Savoy followed the President's speech, most people saw this as an encouraging concrete step. H owever, since France returned twenty-six artefacts to the Republic of Benin and a sword and its sheath to Senegal in 2121, no further objects have been returned. The twenty-seven objects cannot be considered a 'respectable portion of the thousands of African artefacts in France. Twenty-six(26) artefacts from the five thousand objects looted by Dodds and his soldiers in 1892, returned after 130 years, cannot be seen as just and sufficient returns. France must return a more considerable number.

What happened to the recent moral resurgence of many against the unjust colonial systems and racism, which saw even the Director of the British Museum and the Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum express solidarity with Black Lives Matter?

France must fulfil Macron's promise to restitute African artefacts. Whether the delay in further restitution by France is due to the French Parliament's opposition or the French government's failure, is not for us Africans, as outsiders, to apportion blame. We expect the French Government to fulfil its obligations as requested long ago by several UNESCO/United Nations General Assembly resolutions on the Return of Cultural Property to countries of Origin. Germany has done what Macron preached in restoring Benin bronzes to Nigeria. Are French museums going to follow the shameless example of the British Museum? (15)

The ruling elites of African States should be ready to explain to our people how it comes about that after 6o years of independence, we are treated as beggars when we request the return of our looted artefacts from our former colonial rulers. Some generously offer to loan us a few of our artefacts, and we are supposed to rejoice. The former colonial powers treat us as colonials or worse. We do not consider as serious any of the explanations given by the Western States for not returning looted African artefacts. Westerners do not consider Africans as equals. Our contemporary Westerners appear worse than their predecessors in their determination to hold on to ill-gotten gains.

After the former colonial powers’ fundamentally flawed and unsustainable arguments, have Africans presented them with alternate perspectives, apart from appealing to the conscience of the Europeans, which will oblige them to revise their positions? Have Africans demonstrated determination to recover the artefacts that are an essential part of our identity and hence necessary for us to continue our historical development violently interrupted by colonialism? Have we shown that we have absorbed the lessons of our encounter with Europeans since the 15th century?

For centuries, Europeans have been trying to keep Africans out of world history and out of our history by destroying or stealing our artefacts that show our presence in the world and in the rich lands they have exploited for gold, silver, and other resources. At the same time, historians in famous Western universities such as Hugh Trevor-Roper, Regius, professor of Modern History at Oxford University, affirmed that Africans have no history, and scholars who assert the contrary are rejected as heretics. Think about Cheik Anta Diop and the criticism he faced with his thesis about the African origin of Civilization. Does African leadership demonstrate our resolve to be masters of our destiny and lands, including their natural resources and artefacts?

Retrieving stolen treasures from the citadel of stolen property has always been considered challenging. Still, Western museums cannot keep forever the African treasures acquired through violence and theft. The imbalance of power that maintains the colonial haze or daze is already diminishing due to a lack of reasonable justification. The influence of the West is gradually weakening, with Africans gaining more self-confidence and realizing that our continent has vast resources needed in the modern world. Western powers will, in the end, not allow looted artefacts to block possible fruitful agreements. The Germans have learned this in their negotiations with Nigeria concerning the restitution of Benin artefacts. The Swedes have also realized the importance of Nigeria as a strong trading partner and have decided to return thirty-nine Benin bronzes. (16)

Moreover, the growing realization by the Western population of the actual extent of the oppressive colonial system, which is now coming out through the discussions of restitution, would encourage them to support the fight of the African peoples for the return of their looted artefacts.

Like all the other excuses and explanations for not restituting stolen African artefacts, the need for research cannot hide the basic racism underlying the refusal to restitute. Instead of decolonization of Western museums, we see many of their recent activities, presented as cooperation with African countries, more as attempts at recolonization, emphasizing their superiority and access to greater resources.

‘’The restitution of those cultural objects which our museums and collections, directly or indirectly, possess thanks to the colonial system and are now being demanded, must also not be postponed with cheap arguments and tricks.”

Gert v. Paczensky and Herbert Ganslmayr, Nofretete will nach Hause. (17)

NOTES

Titanic' task of finding plundered African art in French museums - Yahoo

'Titanic' task of finding plundered African art in French museums (france24.com)

https://dam.quaibranly.fr/p?t=m1QgtW8xA#/share/media

2. The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics https://web.archive.org/web/20190328181703/http://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_en.pdf p.69.

3. K. Opoku, Macron promises to return African artefacts in French Museums: A new Era in African-European Relationships or a Mirage?

https://www.no-humboldt21.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Opoku-MacronPromisesRestitution.pdf

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/jo/2023/07/23/0169

5. LOI n° 2023-1251 du 26 décembre 2023 relative à la restitution de restes humains appartenant aux collections publiques https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000048668800. Restitutions d’œuvres d’art : le projet de loi à nouveau reporté

(6) Restitutions d’œuvres d’art : le projet de loi à nouveau reporté (la-croix.com)

Le Conseil d’Etat relève un frein aux restitutions d’œuvres d’art acquises par la France dans des conditions abusives

Restitution de biens culturels : Emmanuel Macron annonce une loi, le Sénat a déjà voté la sienne

K. Opoku, Does the Martinez Report Constitute a Pre-Announced Burial of African Cultural Artefacts In French Museums?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1230672/does-the-martinez-report-constitute-a-pre-announce.html

7. David Wilson, The Collections of the British Museum, The British Museum Press,1989, p.97. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes

8. Michel Leiris, Afrique Fantôme,1935, Gallimard, Paris.

9. The literature on violence by colonialism and imperialism is unlimited.

See Dierk Walter, Colonial Violence: European Empires and the Use of Force, 2016, Oxford University Press,

Lauren Benton, They called It Peace: Worlds of Imperial Violence, 2024, Princeton University Press,

Caroline Elkins, Legacy of Violence: a History of the British Empire, 2023, Vintage,

Adam Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa, 1998, Marriner Books,

Casper Erichsen and David Olusoga ,The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism, 2011,Faber and Faber.

Sven Lindqvist, Exterminate All The Brutes, 1996, New Press. K. Opoku, Will Belgium Hear the Call for the Restitution Of Looted African Artefacts? Are Western Museums the Last Bastions of Colonialism and Imperialism?

10. K. Opoku, Humboldt Forum and Selective Amnesia: Research Instead of Restitution of African Artefacts.

https://www.modernghana.com/news/824314/humboldt-forum-and-selective-amnesia-research.html

11. Carsten Stahn, Confronting Colonial Objects: Histories, Legalities, and Access to Culture, Oxford University Press,2023. See especially the chapter entitled, Collecting Mania, Racial Science, and Cultural Conversion through Forcible Expeditions, pp120-178.

Bjorn Thumler, former Minister of Science and Culture in Lower Saxony, stated:

’ Since most of the research on the provenance of the objects is carried out within the framework of PhD projects at universities in Lower Saxony, the project represents at the same time a role model for cooperation between museums and universities contributing to the training of young academics in the field of provenance research on cultural contexts. p.20, in Claudia Andratschke, Lars Muller, Katja Lembke (Eds) Provenance Research on Collections from Colonial Contexts, Principles and Approaches, University of Heidelberg, 2023.

The first professor of provenance research in Germany Dr. Gesa Jeuthe stated:

‘Current provenance research has no standard for defining the origins of an artwork. At the moment, we just list the chain of owners without documentation or context and at the author’s stylistic discretion. This is why the Hamburg Association of Provenance Research is developing guidelines: Every chain of provenance should be scientifically comprehensible, meaning that sources must be cited in a footnote.

These guidelines are important and practical,

but they don’t solve another problem, namely that there is no central, comprehensible, and comprehensive registry of current provenance research on a given artwork. At the moment, a provenance researcher needs to research every clue to a specific provenance, e.g., an art dealer, anew, although another institution may have already done this research. This is inefficient. So, my goal is to cooperate with various institutions to create a system for managing provenance research.’

https://www.uni-hamburg.de/en/newsroom/forschung/2018-02-21-jeuthe-provenienzforschung.html

See also Sarah Van Beurden, Didier Gondola and Agnès Lacaille (Eds.) (Re) Making Collections: Origins, Trajectories, and Reconnections, Africa Museum,2023.

See also Naazima Kamardeen and Jos van Beurden

Law, Provenance Research, and Restitution of Colonial Cultural Property: Reflections on (In)Equality and a Sri Lankan1 Object in the Netherlands, Santander Art and Culture Law Review 2/2022 (8): 181-206 1

Humboldt Foundation curators have even suggested that provenance research must deal with questions such as whether Benin bronze casters considered themselves as free artists or as slave labourers.

K. Opoku, Humboldt Forum And Selective Amnesia: Research Instead Of Restitution Of African Artefacts

12. K. Opoku, Obviously Looted: Benin Bronzes in Museum Of Arts And Crafts, Hamburg, Germany https://www.modernghana.com/news/842018/obviously-looted-benin-bronzes-in-museum-of-arts-and-crafts.html

13. The Benin collections at the National Museum of World Cultures

https://issuu.com/tropenmuseum/docs/2021_provenance_2__benin__e-book

14. K. Opoku, Macron Promises to return African Artefacts in French Museums: A new Era in African-European Relationships or a Mirage?

https://www.no-humboldt21.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Opoku-MacronPromisesRestitution.pdf

15. K. Opoku, How long will the British Government and the British Museum respond to calls for changes in Restitution ?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1135499/how-long-will-the-british-government-and-the-briti.html

Did British Museum Buy Most of Its Thirteen Million Artefacts?https://www.modernghana.com/news/1027473/did-british-museum-buy-most-of-its-thirteen-millio.html

16) The Independent, Sweden Announces Return Of Benin Artefacts https://independent.ng/sweden-announces-return-of-benin-artefacts/ Arise TV, Sweden To Return 39 Benin Artefacts To Oba Of Benin https://www.arise.tv/sweden-to-return-39-benin-artefacts-to-oba-of-benin/

The Guardian, Sweden to return 39 artefacts to Benin https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria/sweden-to-return-39-artefacts-to-benin/

17. Nofretete will nach Hause. Europa-Schatzhaus der "Dritten Welt”, München, Bertelsmann,1984.

IMAGES

Gou, God of War, and metallurgy.

Produced in 1858, by Akati Ekplekendo, Benin, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac at the Pavillon des Sessions, Paris, France. Among the impressive African objects in the Pavillon is the sculpture of Gou, God of iron and of war that the French looted in 1892 from the former French colony, Dahomey.

The Republic of Benin has requested several times the restitution of Gou statue which was not among the twenty-six artefacts France returned in November 2021. The statue of Gou is eagerly awaited in Benin where it will be placed in the newly built museum in the capital, Porto Novo.

President Tolan emphasised the importance of Gou for the people of Benin at the signing of agreements by Benin and France in 2021:

‘’But, Mr. President, Dear President, you will agree with me that the restitution of the twenty-six works that we are celebrating today is but only a step in the ambitious process of equity and restitution of memorial objects exhorted from the kingdoms of the territory of Benin by France.

Mr. President, it is regrettable that this act of restitution, however appreciable, it is not sufficient to give us complete satisfaction.

Indeed, how can you expect that with my departure with 26works that my satisfaction would be complete, while the God Gou, emblematic work that represents the god of metals and metallurgy, the Fa tablet, mythical work of divination of the celebrated sooth sayer Guèdègbé and a lot of other works, continue detained here in France to the great detriment of the actual owners?

But is it subsequently not allowed to hope? Yes, Mr. President.

The hope of returning to our country those works too that I have mentioned and many others, the hope of their recovery to our country is henceforth allowed thanks to you. It is extraordinary’’

https://presidence.bj/actualite/discours-interviews/255/allocution-patrice-talon-occasion-cceremonie-restitution-26-oeuvres-patrimoine-culturel-

K. Opoku, Are we receiving the restitution we seek?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1123962/are-we-receiving-the-restitution-we-seek.html See also K. Opoku, Restitution Day: Remembrance and Reckoning

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1193895/restitution-day-remembrance-and-reckoning.html

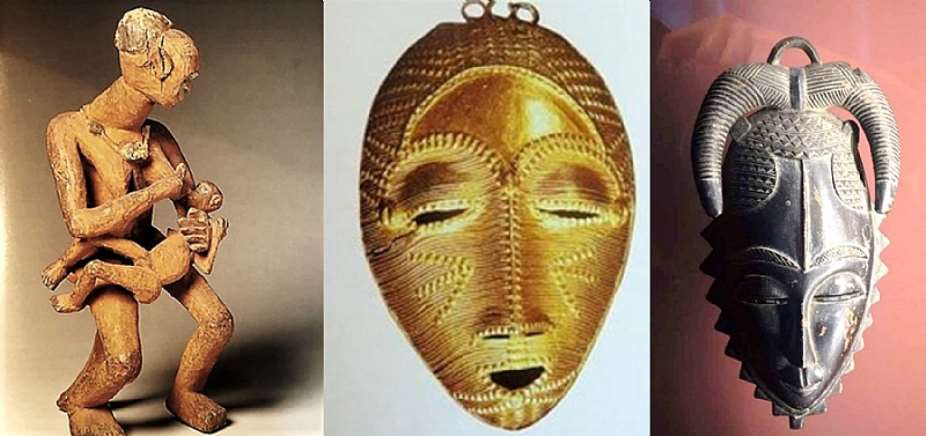

Mask n’domo, Makoka, Mali now in Musée des Arts Africains, Océaniens et Amérindiens, (MAAOA)Marseille, France.

Plaque with two Portuguese warriors, Benin, Nigeria. One of the five thousand treasures looted in

1897, now in Musee du Quai Branly -Jacques-Chirac, Paris, France.

Drum end, Mbembe, Nigeria, now in Musee du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris,

France. How many Nigeria have seen this artefact which French school children can see every day?

Kwayep, Mother and child, Bamilike, Cameroun, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Gold face pendant, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Yahouré mask, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée africaine de Lyon, France.

Akan goldweight, Kumase, Ghana, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jaques-Chirac, Paris, France.

Gelede mask, Yoruba, Nigeria, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Fang mask, Gabon, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Kanaga mask, Bandiagara, Mali, brought by the notorious Dakar-Djibouti-Mission, 1931-1933, now in musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

This is one of three Kono Marcel Griaule, and his team stole from Dogon Villages during the Dakar-Djibouti Mission. It is now in the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques-Chirac, but the visitor is not informed how this powerful and religious object reached Paris from Mali.

Mice divination box, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Headrest, Luba, Democratic Republic of Congo, now in Musée du Quai Branny-Jacques Chirac in Paris, France.

Funerary crown, Yoruba style, Republic of Benin, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Reliquary figure, Gabon, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Female figure, Djenne, Mali, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Double ndoma portrait mask, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Djidji Ayokwe, talking drum, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Palais des Sessions, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France. The drum was expected to have returned early this year to Côte d’Ivoire.

Face mask of the do society in Dyula style. From the Kong region, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France.

Female statue, Aboure/Akan, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée de Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Court of Appeal yet to hear Rev Kusi Boateng's contempt suit against Ablakwa, ca...

Court of Appeal yet to hear Rev Kusi Boateng's contempt suit against Ablakwa, ca...

Why can't Bawumia pick his own running mate; NAPO was imposed on him as his runn...

Why can't Bawumia pick his own running mate; NAPO was imposed on him as his runn...

BoG grilled over $11.2bn discrepancy in remittance data

BoG grilled over $11.2bn discrepancy in remittance data

Call off strike before we hear your case - Labour Commission tells CETAG

Call off strike before we hear your case - Labour Commission tells CETAG

If Afenyo Markin doesn’t present the Free SHS bill today we shall call him names...

If Afenyo Markin doesn’t present the Free SHS bill today we shall call him names...

Afenyo Markin appoints Kwaku Kwartey as spokesperson on Economy Committee

Afenyo Markin appoints Kwaku Kwartey as spokesperson on Economy Committee

Failed leadership fuels monetisation of politics in Ghana – Prof. Kobby Mensah

Failed leadership fuels monetisation of politics in Ghana – Prof. Kobby Mensah

Election 2024: NAPO must work on perceived arrogance – Political Scientist

Election 2024: NAPO must work on perceived arrogance – Political Scientist

Azumah Nelson Sports Complex in sorry state

Azumah Nelson Sports Complex in sorry state

Nurse, Midwife Educators’ Society threaten strike over delayed promotion

Nurse, Midwife Educators’ Society threaten strike over delayed promotion